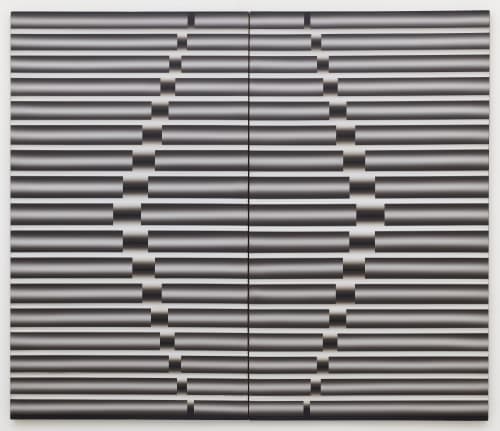

This is a statement that the Korean abstract artist, Lee Seung Jio (1941-1990), made in 1971, a few years after he gained attention in Korea for his cooly geometric abstract paintings of cylindrical forms:

Some call me “Pipe Painter.” I neither welcome nor dislike the distinction. The nickname might be a reference to the illusionistic objecthood created by the repetition without the premise of the motif based on a specific subject. Of course, the pipes are not conjured as a symbol of modern civilization.

The reason I am citing this is because Lee’s paintings, which are being shown in a posthumous New York debut exhibition, Lee Seung Jio: Nucleus at Tina Kim Gallery (February 20–April 4, 2020), are a revelation on a numerous levels.

First, they introduce us to the work of an artist who rejected both Abstract Expressionism and Monochromatic painting — the dominant styles in Korea during the early 1960s — and essentially invented his own hybrid style at a young age, which he continued to explore until his premature death at fifty.

Second, starting with Kim Whanki (1913-1974) and continuing through Yun Hyong-keun (1928–2007), Kim Tschang-yeul (b. 1929), Park Seo Bo (b. 1931), and Lee Ufan (b. 1936), innovative abstract painting was always energetically alive in Korea, even if for many years it was not widely recognized on the world stage, especially in the US. While these five artists have become known and celebrated in the West, the strongest painters of the next generation still remain to a large extent under-known.

The exhibition contains 14 paintings dated between 1968 and 1988, a span of two decades. By including works from different periods, the exhibition makes one thing apparent: despite the strict limits he established for himself, Lee never got stuck. This cannot be said for other abstract artists who gained attention in the 1960s. Older Americans, such as Gene Davis (1920-1985), Jules Olitski (1922-2007), and Kenneth Noland (1924-2010), are good examples of artists who got stuck in a signature style or technique, which was unquestioningly obeisant to painting’s flatness.

Lee undid the tyranny of flatness by introducing gradated tones into his bands, thereby melding two seemingly incommensurable vocabularies: volumetric surfaces with flat ones. His hybrid language suggested a sympathy with Op Art, particularly artists whose motifs consisted of stripes, and with the German artist Konrad Klapheck (b. 1935), who is known for his oversized, hyper-exact, stylized paintings of typewriters, sewing machines, telephones, and other machines.

Rather than finding the rhythmic repetition of Lee’s forms comforting or reassuring, I was unsettled by their demand to call forth two ways of seeing. It was as if there is no secure place from which to view Lee’s work, and this I feel was deliberate on the artist’s part.

Lee called his paintings “Nucleus” and often numbered them. Together, the gradated bands, which seem be reflecting light off the surface, and the flat, solidly colored bands juxtaposed against them form the “nucleus” or most central, irreducible part of each painting. This suggests that Lee, as influenced as he was by Western postwar painting, which he studied in the painting department of Hongik University, Seoul, Korea, rejected all-over compositions made of similar marks or forms.

The optical effects are unsettling as the paint shifts from gradated bands (or volumetric presences) to flat bands of color, which appear ghostly, as if they are beginning to dissipate along their outer edges, as in “Nucleus 84-49” (1984) and “Nucleus 85-1” (1985).

Within such a rigorous composition, slight textural variations in the surface, from hard and flat to viscous and grooved, are captivating. The attentive viewer is apt to end up scrutinizing every inch of the composition, as the differences both underscore and complement the divergent vocabularies that Lee has deftly joined together. More than once I was struck by the grooves left by the brush as it runs evenly and unhesitatingly across a clearly delineated area.

Lee’s painterly control is apparent from a distance but also from close-up. In contrast to many Op artists, as well as painters who were developing an Abstract Illusionist vocabulary, such as Al Held, Lee was not interested in suppressing evidence of the hand. Rather, the virtuosity of his control conveyed a tension between expressiveness and reticence, assertion and discipline.

—John Yau